John Ford’s film was based on Alan Le May’s novel of the same name. The author researched dozens of Native American child abduction cases in Texas, but his main source of inspiration was Cynthia Ann Parker, a nine-year-old girl taken when a 700-strong raid descended on her family’s stockade in 1836 (via Texas Public Radio). Five of her relatives, including her father and grandfather, were killed, and the raiders made off with her and four other young people. Her uncle James Parker spent the next 24 years searching for her, during which time he managed to get the other four back.

Cynthia Ann was eventually discovered when the U.S. Cavalry and Texas Rangers launched a murderous raid on a Comanche settlement. The attackers were about to kill her too but noticed she had blue eyes, a rarity among Comanches. During her time with the tribe, she married a Chief and had three children. She was captured and taken away with her daughter, Prairie Flower, but was never able to re-adjust to a world she no longer felt a part of.

Ethan’s motives in The Searchers

The young women who were taken by Native Americans in these abduction cases ended up, willingly or unwillingly, having sex with their captors. Necessarily for the era, “The Searchers” largely skirts around saying that outright, yet implied sexual assault looms heavily over the entire film and drives Ethan Edwards forward on his mission. As we learn early on, he doesn’t have much time for Indigenous people in the first place, yet the idea that Debbie has been violated by her captors twists his hatred even further.

In his eyes, such an existence for his niece is a fate worse than death, as we see in his horrified reaction when he and Martin visit a fort where young women recovered from the Comanches are being held. They are portrayed as being deeply traumatized by their experience, but Ethan has no pity; when a soldier remarks it’s hard to believe they are white women, he fires back bitterly, “They ain’t no more.”

As he sees it, Ethan’s goal to murder his niece is almost an honor killing. It says far more about how he feels about her becoming a sexual object for the Comanches rather than how she might feel about it. He even tries to justify his intent, stating, “Living with Comanches ain’t being alive.”

Ethan’s racist views are shared by some of the more benign characters in the film. Martin’s love interest Laurie Jorgensen (Vera Miles) seems like Ethan’s antithesis, but when she learns they have discovered Debbie’s location, she reveals her own attitude on the matter: “Fetch what home? The leavings of a Comanche buck, sold time and again to the highest bidder, with savage brats of her own?” She goes on to say that Edwards will put a bullet in Debbie’s brain and, what’s more, the girl’s own mother would have wanted the same.

Did Ethan and Martha have a thing?

When Ethan Edwards returns home at the beginning of “The Searchers,” there definitely seems to be a little awkwardness. His brother Aaron welcomes him with a few stiff handshakes while Ethan shares several long, lingering glances with Martha. They don’t say much to each other, but there is clearly some tension between them. She can’t keep her eyes off him at the dinner table and when Reverend Captain Samuel Clayton (Ward Bond) comes to enlist the men’s help in tracking down Jorgensen’s cattle, he tries not to notice as Martha lovingly caresses Ethan’s coat before sharing a wordless, emotional goodbye.

These moments have resulted in the popular theory that Ethan had an affair with Martha before leaving to join the Confederate Army and that Debbie is his daughter. The timeline checks out because Ethan has been away for eight years and it is made clear that the girl is now eight years old. Of course, the family might just greet Ethan’s return with trepidation because he’s a domineering a******, but an affair would certainly explain the awkwardness. If it seems obvious to us that something went on between Ethan and Martha, surely Aaron would also pick up on the pair making eyes at each other right under his nose.

If Debbie is Ethan’s daughter, it would justify his feelings a little better. He’s good with Aaron’s kids, yet he noticeably softens in the presence of Debbie. An uncle can have strong feelings for his niece, of course, but it would be more understandable that a tough guy like him would melt at the first sight of a daughter he’s never met before. It would also make his hellbent desire to track her down more potent, and his goal to kill her even more abhorrent.

Racism in The Searchers

John Wayne starred in dozens of Westerns during his lengthy career, but he very rarely played the bad guy. One of his darkest roles came in “The Searchers,” his 14th and greatest collaboration with John Ford, the director who helped the Hollywood icon make his name in “Stagecoach.” It was a film that inverted Wayne’s heroic screen persona by casting him as Ethan Edwards, a bitterly racist former soldier who spends many years on an obsessive quest to track down his niece after she is abducted by Comanches.

For a director-star combo that had often portrayed Native Americans as a faceless marauding horde in many of their earlier pictures, “The Searchers” is a soulful and sometimes awkward attempt to reckon with that past and, in turn, America’s legacy of genocide and Manifest Destiny. While its comedic moments seem to belong to another film and its use of Redface is cringe-inducing, the main thrust of Ethan’s relentless search, driven by his hatred for Native Americans, was ahead of its time and remains incredibly pertinent to this day. It wasn’t the first Revisionist Western, but it is one that challenged the norm in the fading era of classic Hollywood horse operas, introducing shades of grey to a genre that previously boiled down to simplistic “white hats vs. black hats” or “cowboys vs. Indians” narratives.

After almost 70 years, despite changes in attitudes and its star becoming widely reviled for his problematic views on just about every minority group including Native Americans, it maintains its status as one of the greatest American movies ever made, still riding high in Sight and Sound’s esteemed Top 100. To top it all off, the film closes with one of the most iconic shots in cinema history. But what does that famous ending mean?

The set up

“The Searchers” opens with a breathtaking vista as Ethan Edwards (John Wayne) returns to his brother’s isolated homestead after an eight-year absence. His past is shadowy; after finishing on the losing side in the Civil War, he became a decorated campaigner in the Mexican revolutionary war and carries a big stash of Yankee gold that may well be stolen.

He is cautiously welcomed by his family. There is brother Aaron (Walter Coy) and his wife Martha (Dorothy Jordan), their eldest son Ben (Robert Lyden), daughters Lucy (Pippa Scott) and Debbie (Lana Wood), and Martin (Jeffrey Hunter), a young man with Cherokee blood who was adopted by the family when he was orphaned as a baby.

His homecoming rest is short-lived. The cattle of his neighbor Lars Jorgensen (John Qualen) are stolen and Reverend Captain Sam Clayton (Ward Bond), who Edwards knew during his time in the Confederate Army, is rounding up a posse to recover the animals. The theft turns out to be a decoy by the hostile Comanche tribe to draw the men away from their homes, and Ethan and Martin find the ranch burnt to the ground upon their return. The family has been massacred and the two girls have been abducted.

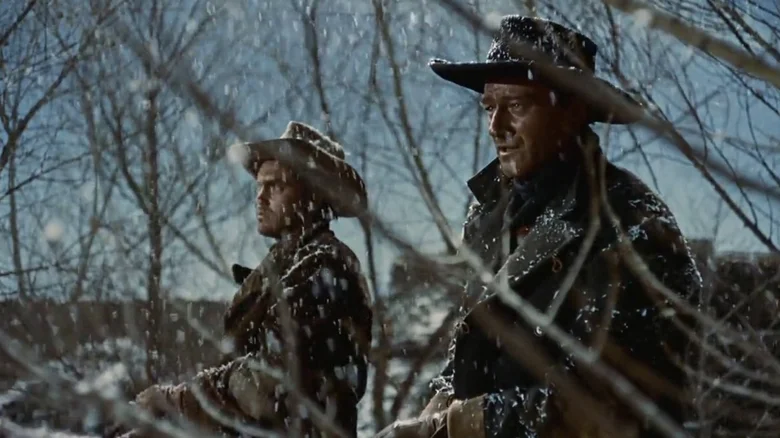

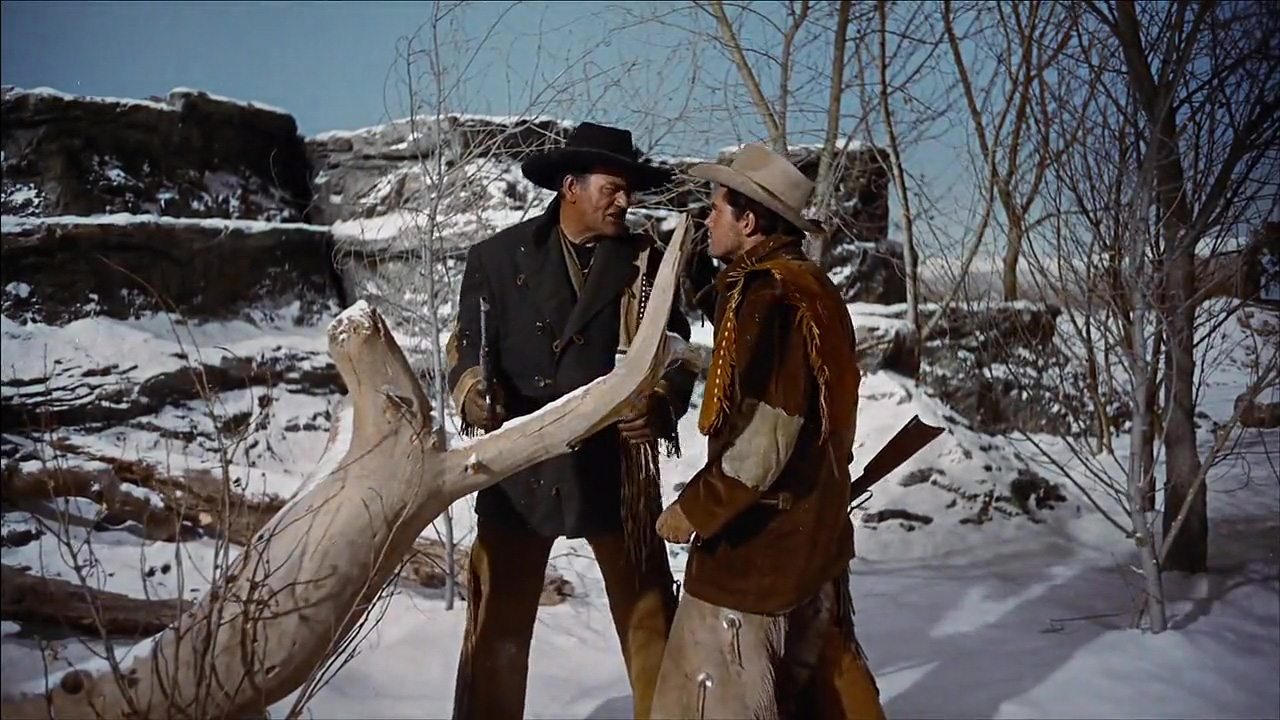

Initially assisted by a dwindling posse that includes Lucy’s boyfriend Brad Jorgensen (Harry Carey Jr.), Ethan and Martin spend years on the trail of the Comanches trying to discover the whereabouts of the girls. Over time, Ethan’s attitude toward the Natives becomes increasingly hateful and his motives change into something far more murderous: Instead of rescuing the young women, he plans to murder them since they’ve been violated by Comanche “bucks.” Once they learn Debbie is being held captive by Scar (Henry Brandon), a fierce and proud chief with his own vengeful agenda, will Ethan really carry out his threat to kill her?

The true story behind The Searchers

The story of “The Searchers” was based on a strange phenomenon from the dangerous days of the American frontier when pioneers frequently found themselves under attack from the Indigenous Americans they had taken the land from. By way of retribution for the atrocities committed against them by the settlers, tribes launched deadly raids against isolated settlements, slaughtering families and snatching their children.

Much like the protagonists in John Ford’s film, surviving family members often spent decades searching for their missing loved ones; in the case of Frances Slocum, her brothers kept up the hunt for 60 years before they finally saw her again. Unlike little Debbie, many of the abductees fully integrated into their new communities and were unwilling to come home.

It can be a little tricky grappling with “The Searchers” from a modern perspective, especially armed with the knowledge that John Wayne himself was a racist and a bigot. There is no doubt that Ethan Edwards is a bitterly racist character; he is openly contemptuous of his adopted nephew Martin because he has Cherokee blood and would rather slaughter buffalo rather than let them provide food for Native Americans in the winter. Most alarming is the scene when he vindictively desecrates the corpse of a Comanche warrior by shooting out the eyes, condemning its soul to wander among the winds rather than reach the spirit land.

If Ethan was portrayed by an actor who wasn’t such an outspoken bigot in real life, it would be easier to commend Wayne’s performance for flipping the attitudes of his earlier Westerns where Native Americans were often dispatched like zombies or evil aliens, much in the same way Clint Eastwood interrogated his violent “Man With No Name” persona with “Unforgiven.”

As Roger Ebert pointed out, however, many audience members at the time would have uncritically bought into the film’s portrayal of the Comanches as savage murderers, perhaps even feeling that Ethan’s actions and intentions were justified. As for Wayne, how much of Ethan’s malice came from the character, and how much from himself? After all, he was the man who reportedly needed holding back from assaulting Sacheen Littlefeather when she gave a speech on behalf of Marlon Brando at the 1973 Oscars and said in his infamous 1971 Playboy interview:

“I don’t feel we did wrong in taking this great country away from them… Our so-called stealing of this country from them was just a matter of survival. There were great numbers of people who needed new land, and the Indians were selfishly trying to keep it for themselves.”

The Searchers Ending Explained

Ethan Edwards seems pretty clued up on Native American customs and language, but even holding more knowledge about their culture than the average rancher does nothing to awaken any empathy toward them. It only seems to fuel his hatred even more, and he genuinely seems ready to gun Debbie down when they first find her before Martin stands in the way. Thankfully, when they return with a posse to raid the Comanche camp, he has a change of heart and embraces her, saying, “Let’s go home, Debbie.”

He returns his niece to the Jorgensen ranch and suddenly finds himself redundant and out of place. The famous final image mirrors the first shot of the movie, viewed from inside the darkened interior of the home. The family all enter, not giving him a second glance. Even Martin, whom he has spent so many years on the trail with, walks past him with Laurie as if he isn’t there. It may be he doesn’t feel welcome anymore after so long away or the family resents him for his belligerent behavior, but it is presented as if he has simply ceased to exist.

Prefiguring the world-weary outlaws of “The Wild Bunch” 13 years later, Ethan has become a figure out of time, an anachronism of the Old West with no real place in the domesticity of the modern world. With his close family dead and finding himself on the losing side in the Civil War, he is lost and alone. Unable to cross the threshold of the home, he cradles his arm forlornly before turning and walking away across the sands, recalling the earlier scene when he shoots out the Comanche’s eyes. Like that fallen warrior, Ethan Edwards is doomed to wander between the winds.