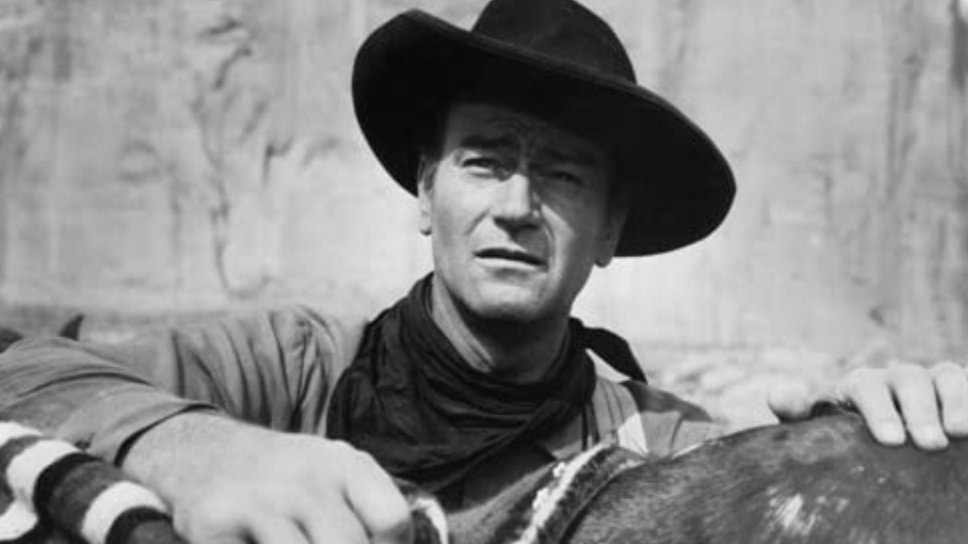

It’s been nearly half a century since John Wayne last donned his iconic stetson hat to play a Western hero, but the actor’s name is still synonymous with America’s collective image of the Wild West cowboy. During the golden age of Hollywood Westerns, Wayne was the most recognizable gunslinger around, and he won the hearts of millions playing tough, imperfect, sometimes irascible men fighting their way through the rough-and-tumble frontier. From “Stagecoach” to “The Shootist,” Wayne frequently embodied what many remember as the prototypical on-screen cowboy.

In reality, though, Westerns existed on screen even before Wayne made his cinematic debut in the 1920s, and the actor wasn’t particularly fond of the way they tended to be portrayed. “I made up my mind,” Wayne told Maurice Zolotow for his biography “John Wayne, Shooting Star,” “that I was going to play a real man to the best of my ability. I felt many of the Western stars of the 1920s and 1930s were too goddamn perfect.” Beginning in 1934, censorship from the now-infamous Hays Code put a moral responsibility on Hollywood that restricted violence on-screen. Even before the Hays Code, many on-screen cowboys (like other early film figures) had a sense of costume to them, and Western heroes often looked more like playactors than real down-and-dirty cowpokes.

‘They were too goddamn sweet’

Wayne took issue with this. “They never drank nor smoked. They never had a fight,” the actor lamented in Zolotow’s biography. “A heavy might throw a chair at them, and they just look surprised.” Wayne famously played some questionable antiheroes along with his white-hat roles, as in John Ford’s “The Searchers.” That 1956 film grappled with — though didn’t completely address — long-brewing questions about violence, racism, and gender dynamics within the genre. Wayne’s Ethan was a revenge-driven antihero who shattered the illusion of the morally pristine cowboy once and for all.

“They were too goddamn sweet and pure to be dirty fighters,” Wayne says of the early film cowboys. He adds:

“Well, I wanted to be a dirty fighter if that was the only way to fight back. If somebody throws a chair at you, hell, you pick up a chair and belt him right back. I was trying to play a man who gets dirty, who sweats sometimes, who enjoys really kissing a gal he likes, who gets angry, who fights clean whenever possible but will fight dirty if he has to.”

Ironically, this portrait of a cowboy sounds just as oversimplified and idealized now as the 1920s cowboys did to Wayne at the time. The Western genre has mostly died out in recent decades as its traditional templates of racism, nationalism, and machismo have fallen out of fashion. When it has returned, it’s been with fresh spins on the cowboy story that reveal facets of the archetype rarely put to screen before, as with Ang Lee’s “Brokeback Mountain” and Jane Campion’s “Power of the Dog.” Both of those movies center the stories of gay cowboys, a notion that Wayne himself would likely find blasphemous if his homophobic reaction to “Midnight Cowboy” is any indication.

What counts as ‘phony’ anyway?

Wayne isn’t alone in his homophobic attitudes. The idealization of the “manly man” cowboy has always gone hand in hand with an unstated put-down of anyone less-than, whether that’s actual gay cowboys (who did exist, of course) or simply men who didn’t perform the gruff, reckless sort of physical masculinity that Wayne popularized on screen. Just last year, actor Sam Elliott made comments about “Power of the Dog” that echoed Wayne’s from the early ’70s, criticizing the shirtless cowboys and “allusions to homosexuality” in the film. “What the f*** does this woman from down there, New Zealand, know about the American West?” Elliott said on Marc Maron’s “WTF” podcast. In his biography, Wayne condemns the squeaky-clean cowboys of the era before him. “I didn’t want to be a singing cowboy,” he says. “It was phony.”

The ironic thing about these juxtapositions between the cowboys Wayne and Elliott don’t like and the “real” men they idealize is that both treat the less overtly masculine portrayals as inauthentic in a way that offends them personally — as if they themselves were real cowboys, not actors who grew up in Portland and studied at USC, respectively. This isn’t to say that Wayne and Elliott aren’t qualified to have strong opinions on the matter, but that Westerns have always dealt in American mythology, which is ever-shifting and much more complex than a single portrayal of masculinity.

There’s no way of knowing how Wayne would feel about the recent return of movies about cowboys aren’t brawlers, but we do know that Wayne was aware of the way he shaped that image in the first place. “You could say, I made the Western hero a roughneck,” he says in “John Wayne, Shooting Star.” And the genre was never the same again.