It is commonly believed that one industry immune from the great crash of 1929 and subsequent economic depression was the movie business. People still wanted the escapist entertainment of a film despite (or even because of) the grim economic and social situation, it is said. This was, in fact, not at all the case. While Hollywood did make a comeback in the late-1930s, the whole business suffered severely in 1929 and the immediate aftermath

Four thousand movie theaters closed in 1931 and 1932, and 43,000 people who worked in them lost their jobs. Studios too laid off 20% of their staff and those who remained had their pay cut. Audiences fell 12% despite a 30% cut in ticket prices. It was in this climate that the enormously costly The Big Trail (1930) helped push Fox over the financial brink. Young John Wayne might well have thought that his lead role in that picture would have launched him to Hollywood stardom. It was not to be.

Instead, he got a contract with Columbia, one of the ‘Little Three’ studios (Columbia, Universal, United Artists), not one of the so-called Big Five (MGM, Fox, Warners, Paramount, RKO). Columbia boss Harry Cohn threw himself gleefully into cost-cutting. Theaters were now offering double-bills to attract the customers, and Cohn was happy to provide them with ultra cheaply produced programmers that he could turn out on a production line as rapidly as possible. Westerns were ideal material.

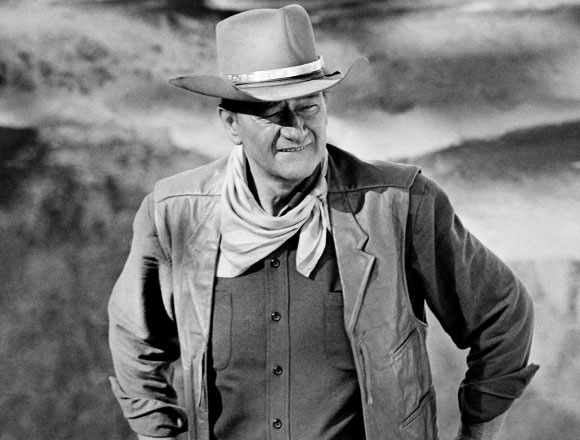

Wayne was in three, The Range Feud (1931), Texas Cyclone (1932) and Two-Fisted Law (1932). I say he was “in them” because he did not star. They were B-Westerns featuring Buck Jones (The Range Feud) and Tim McCoy (the other two). Finally he was fired. Wayne later claimed that he was dropped for making up to an actress that Cohn had his eye on (Duke said it was “a goddam lie”) but it is also possible that the names of the aging but well-known cowboy actors Jones and McCoy brought in the crowds and the young, handsome star of The Big Trail, still relatively unknown, was an unnecessary luxury. And Cohn didn’t do unnecessary luxuries.

In any case, the three movies are pretty bad.Low-cost B-Westerns in the early 1930s didn’t have to be bad. True, many of them were formulaic and predictable but a lot of them had zip and energy. Think of those Zane Grey stories Paramount filmed with Randolph Scott, directed by Henry Hathaway. They were a lot of fun. Or the six Westerns that Wayne himself made with Warners in 1932/33; some of them, like The Telegraph Trail, were really good. The three Columbia efforts, however, all directed by D Ross Lederman, were shockers. Lederman was Cohn’s kind of director: he had a rep for bringing films in early and under budget, never mind the quality.

To give you an idea of The Range Feud, the opening frame shows a sign upon which is printed BUCK JONES RANGE FUED. That’s how slapdash it is. [One reader asures me that this was not the original Columbia title but was a shoddy later TV one. That may be so.] But it doesn’t improve from there. The acting is pretty wooden. Only Wayne has a go at some naturalness. All the other actors, without exception, ponderously shout the lines they have learnt (or are reading) in a monotonous drone.

Any Midwest amateur dramatic society would have done better. Will Walling and Susan Fleming are probably the worst – they are laughably bad – but there’s no one any good really. Buck Jones (aged 40 but looks about 55) in his giant hat is a plodder. Buck did some great early work, directed by the likes of John Ford and William A Wellman, but not here.

The worst thing about the movie is that there is hardly any action. It’s all talking. Blah, blah, blah. This really has to be one of the worst B-Westerns ever made. Thanks, Harry.Texas Cyclone was little better. Tim McCoy’s career was in its twilight years and was soon to nose-dive to Poverty Row studios and obscurity. No wonder, really, with movies of this quality. Wayne has a minor part as an honest cowpoke on a ranch whose foreman and crew are rustlers. Once again, action takes second place to talking – dangerous for any Western and death to a B oater which has nothing else (certainly not quality acting) to offer. What’s the opposite of a Cyclone?

Two-Fisted Law has the most juvenile dialogue you have ever heard (I promise). Tim McCoy loses his ranch to bad guy Wheeler Oakman and goes off to prospect for silver. Two years later – oh, you don’t want to know. John Wayne has an even smaller part. He plays a character called Duke. McCoy (his hat is also giant) is a better actor than Buck Jones in The Range Feud, I will say that, but it’s hardly praise.

The only half-interesting thing about the two Tim McCoy movies is that Walter Brennan, in his mid 30s, plays a crooked lawman in both. John Wayne may not have thought so at the time but getting fired from Columbia was the best thing that could have happened. He managed to land a contract with Warners and while the movies there too were quickly-produced B-Westerns, they were of vastly greater quality than the Harry Cohn ones.

Duke disliked Harry Cohn ever after, even to the point that when, twenty years later, Cohn had a great property, The Gunfighter, which Wayne, by now a famous Hawks and Ford big star, desperately wanted to do, he wouldn’t because Cohn was offering it and he wouldn’t work with Cohn. In the end, Cohn sold it to Fox and Henry King directed Gregory Peck in one of the greatest Westerns of all, in 1950. You could say that Wayne cut off his nose to spite his face – or that he stood, decently, on principle.