‘Unforgiven’ was a masterpiece of the genre, and the culminating shootout was its pinnacle.

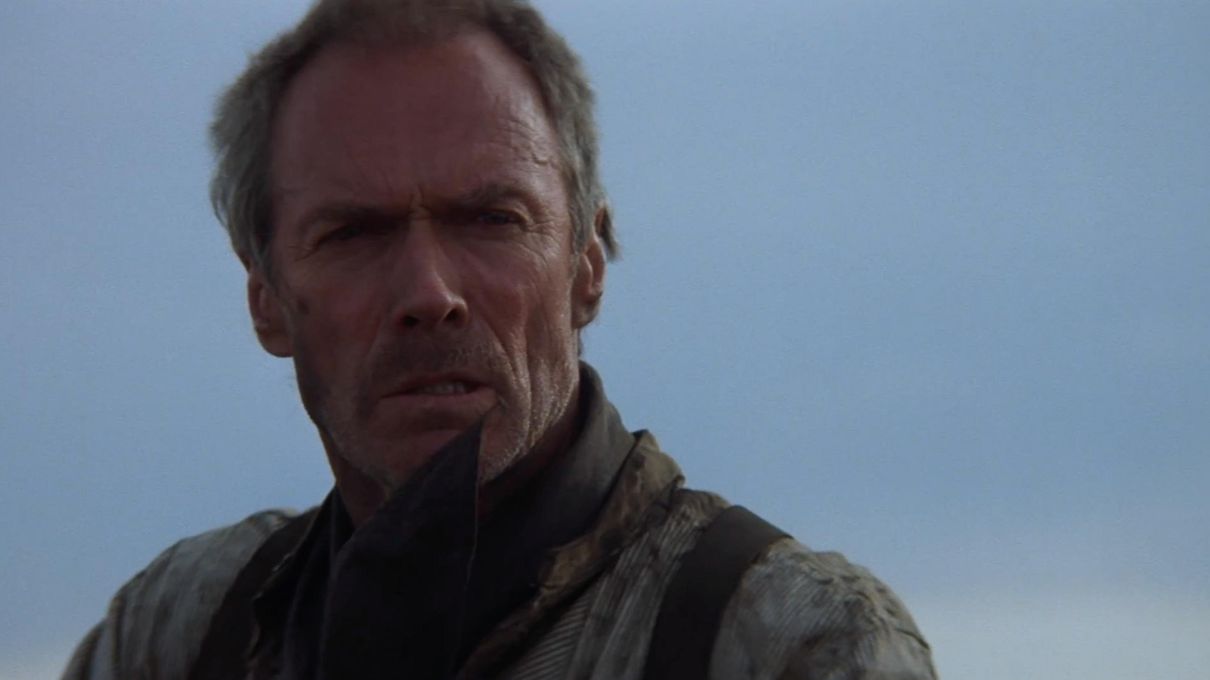

In his magnum opus, and arguably the finest western of all time, Unforgiven, Clint Eastwood came back to his roots as a vengeful cowboy who relapses into his contemptuous past. With an Academy Award-winning turn from Gene Hackman, and stellar performances from Morgan Freeman, and Richard Harris, the Best Picture of 1992 was nothing short of a cinematic masterpiece. Met with immense critical acclaim, and its influence radiating waves throughout the community of film, it presented a deconstruction not only of Eastwood’s entire career, but also of the genre and its inherent glorification of the wild west. Despite its inherent poeticism as a whole, the picture manages to top its own artistry by presenting viewers with the best ten minutes in all of Western cinema.

What is ‘Unforgiven’ All About?

Eastwood plays William Munny, a widower who has all but given up on the life of crime. Formerly a feared murderer and outlaw, he has retreated to living as a farmer to make ends meet, and appears to be resentful of his existence. Visited by a brash young gunslinger named The Schofield Kid (Jaimz Woolvett), he is offered to kill a couple of prostitute-defacing outlaws. Reluctantly, he accepts this one final job in order to give his children a better life, and enlists the help of his old friend Ned Logan (Morgan Freeman).

Meanwhile, in the town of Big Whiskey, the location of the alleged abuses, Sheriff Little Bill Daggett (Gene Hackman) is imposing a restriction on firearms. He makes an example out of English Bob (Richard Harris), who attempts to take the same bounty presented by the prostitutes. Bob’s accompanying author, W.W. Beauchamp (Saul Rubinek), witnesses the downfall of his initial subject for the book he is writing, and switches over to Little Bill as his new inspiration.

During the night, Munny, Logan, and the Kid arrive at Big Whiskey. While Ned and the Kid treat themselves to the services of the prostitutes, a feverish Will encounters Little Bill in the saloon and beats him to within an inch of his life, and telling him to never come back to this place again. After they nurse Will back to health, they successfully kill one of the perpetrators, but Ned decides to quit. The Schofield kid then kills the remaining outlaw, but reveals that it shook him. In the midst of this epiphany, Will and the Kid are informed that Little Bill has slowly and painfully killed Ned. This infuriates Munny. He takes a huge swig of whiskey, and prepares to avenge the death of his friend, setting the stage for one of the most exhilarating sequences in Western history.

Armed with a double-barreled shotgun, an intoxicated Munny bravely enters Greely’s. Soaking wet from the rain, he cocks the gun and asks who owns the place. Skinny Dubois (Anthony James) bravely answers, and he is subsequently shot. In the ensuing shootout, Munny critically wounds Little Bill, and eliminates all those who chose to stand in his way. With one final shot, he kills Little Bill and sends a chilling warning to those who wish to stop him.

The Significance of the Shootout at Greely’s

Basking in the glory of the signature Clint Eastwood machismo, and his immense charisma as a gun-slinging cowboy, the shootout at Greely’s epitomizes what the western genre is all about. Simply put, it is the best series of events unfolding in a Western movie, and it’s not even close. The heavy rain pouring on Munny, and the deafening sounds of thunder accompanying this angel of death as he approaches his eventual victims, is indicative of its enticing darkness.

If one were to talk about the artistic patterns of a Western, they would immediately come to several ideas: tough rugged men engaging in quick-draw duels, saloons filled with gambling, and a penchant (or even romanticization) of the notion of violence. There have been many westerns that have presented this, with the versions in the world of Sergio Leone

and Sergio Corbucci immediately coming to mind, but there is a certain fluidity in Eastwood’s brushstrokes. While the other versions of these final duels present the characters as having dead shot accuracy, Unforgiven lends a bit of realism. Guns are jamming, shots are missing, and the presence of hesitancy in those involved presents a life-like picture of how rough and gritty the West truly is. The cold-blooded killers will come out on top, and those who think twice will be pummeled by lead. Munny is the victor. He owns up to killing women and children, and he makes no qualms about it. There is no greater fear than standing in front of a man who simply does not give a damn.

There is also a reflexive nature in how this finale is presented. Using a Hitchcockian allure, expanding the figurative rubber band of suspense until it eventually breaks, Eastwood deconstructs and ultimately destroys the notion of his own past. Little Bill figuratively represents his old Dirty Harry persona: a lawman who willingly goes out of the rule book and abides by his own set of policies. Once audiences realize this, it invites them to revisit his own body of work, and asks them to ponder on their importance. By brutally killing Little Bill, Eastwood is shedding his own skin, representative of his patented auteurial characteristics. He does this while coming full-circle.

He uses a Western to destroy the image of his old characters, directly or indirectly being Western characters themselves. Beauchamp’s attempts to approach Munny as his new subject of writing, only to be met by genuine fear, exemplifies this destruction. There isn’t anything fun out of all of this. Rather, the actions of his old portrayals, and Munny’s rampage, is suggested to be re-appraised with a condemning lens. It’s a magnificent piece of meta-cinema, urging callbacks and fascinating re-watches of his films.

A Commentary on American History

Perhaps even more significant than its subversion of the genre is its clever commentary on American history. While there is an enhanced focus on the shootout itself, the moments that come after it are equally essential. When Munny comes out of the saloon armed with Ned’s Spencer Rifle, he sends a strict message of caution to all the survivors: they better not hurt any more prostitutes, or he will come back and kill every last one of them. All this occurs while the American flag is behind him. This may be construed as a critique on the country’s history.

The story of America is filled with instances of bloodshed. While some may consider the carnage to be borne out of necessity, particularly in establishing the USA’s freedom and independence, it upholds that the examination of the country’s development will always be riddled with tales of gruesome violence. Him riding into the darkness on a pale horse, like the grim reaper, is the poetic cherry on top. Violence, like Munny himself, will always be there. If the circumstances call for his appearance, then it shall come back with a fury like no other. Sometimes it is rightful, and sometimes it is not, and much like how Munny has been portrayed, it will always be like walking on the tightrope of morality.

In its profound ending, Clint Eastwood takes the greatness of the Western, and simultaneously uses its flair while turning its conventions on its head. All of this while offering his own thoughts on the formation of his own country. It is a virtuoso at the very peak of his own authorship, and the result a testament to his own sensibilities as a filmmaker. Eastwood has made stellar Westerns before, but in Unforgiven, he shows that it is indeed a hell of a thing killing a man. Deserve’s got nothing to do with it, it simply is the championing sequence of a genre that has erected, and continues to be one of, the foundations of American cinema.