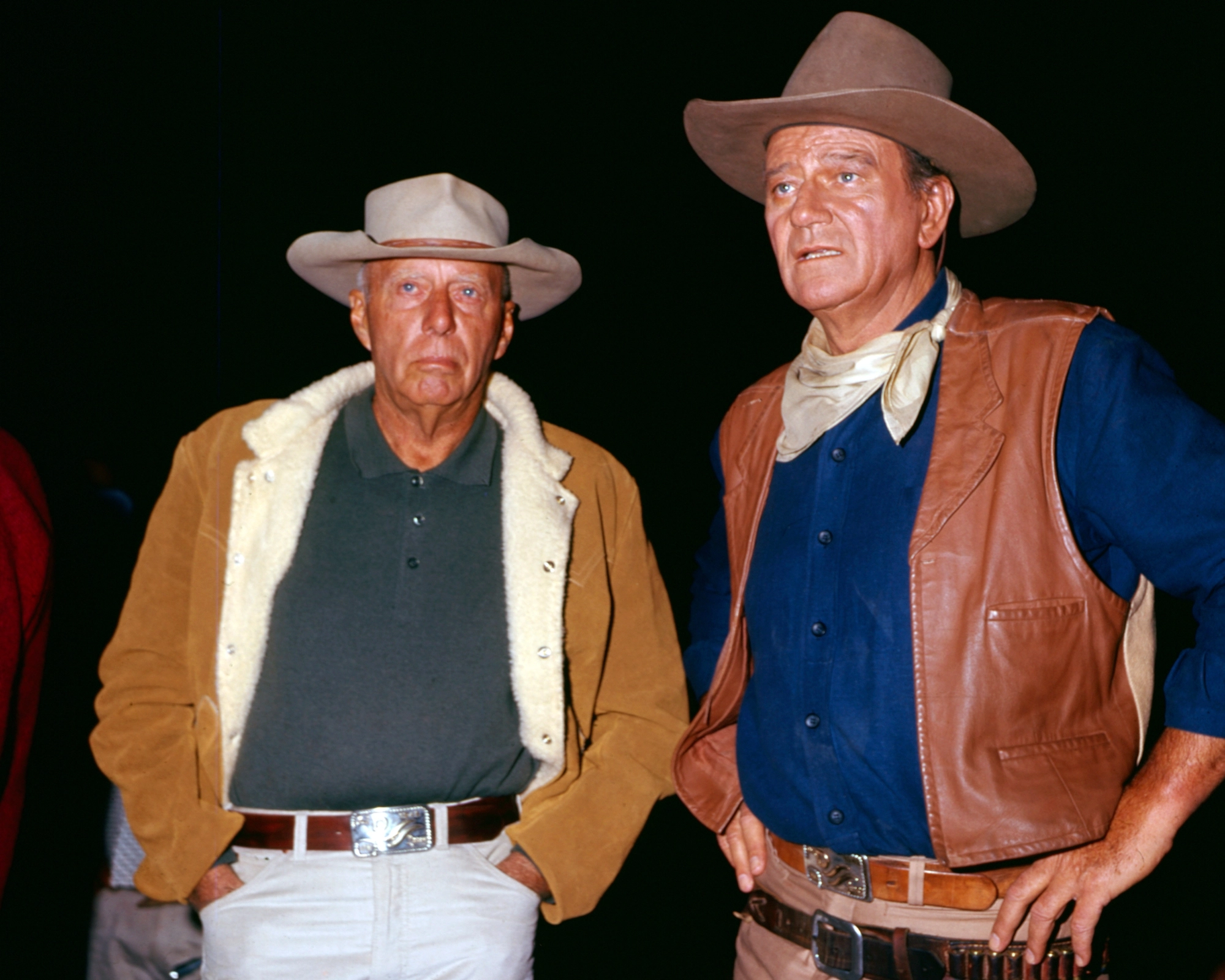

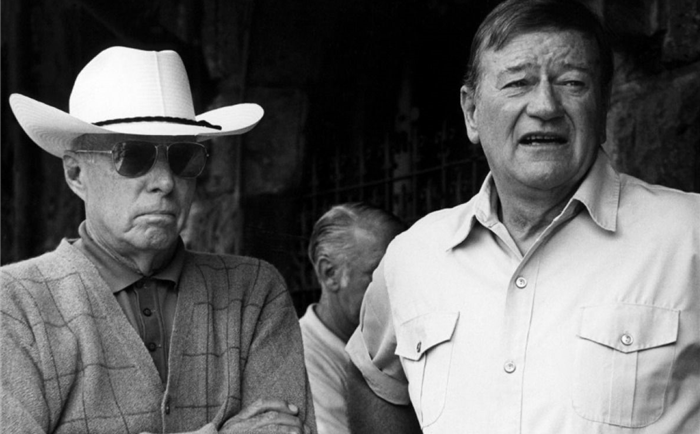

Howard Hawks described the special relationship he had with John Wayne in the following way: “The last picture we made, Rio Lobo, I called him up and said, ‘Duke, I’ve got a story.’ He said, ‘I can’t make it for a year, I’m all tied up.’ And I said, ‘Well, that’s all right, it’ll take me a year to get it finished.’

He said, ‘Good, I’ll be ready.’ And he came down on location and he said, ‘What’s this about’ And I told him the story. He never even read it. He didn’t know anything about it.” Wayne confirmed this story: “I just ask the director which hat he wants me to wear and which door I come in.”

Although many reviewers believed Wayne’s ability was wasted in Rio Lobo, their thinnest collaboration and a much worse Western than either Rio Bravo or El Dorado, this implicit, almost naïve, faith in Hawks came at a cost.

Significantly, Howard Hawks himself attributed the picture’s failure to the casting, “I didn’t like it. I didn’t think it was any good. I only made it because I had a damn good story and the studio couldn’t afford to put a man as good as John Wayne in it, so we ended up with the cast we had.”

Rio Lobo’s cast, one of the worst in a Wayne movie, included such unknown or inexperienced actors in leading parts as Jorge Rivero, Jack Elm, and Chris Mitchum.

Hawks directed Westerns and action movies with other actors, such as The Big Sky, starring Kirk Douglas, but they were pale compared with those starring Wayne. “If you try to make a Western with somebody besides Wayne,” he observed, “you’re not in the sphere of violence and action that you are when you’ve got Wayne.”

Of the actor’s greatest assets, Hawks singled out his “force” and “power” and the fact that “he thinks quickly and thinks right.” Wayne was considered by far the best: “When you have someone as good as Duke around, it becomes awfully easy to do good scenes because he helps and inspires everyone around him.”

Curiously, Lee Marvin did not think so; when he asked Hawks to direct him in Monte Walsh, he told him he wanted it to be a Lee Marvin, not a John Wayne, Western. Hawks is reported to have answered with a good deal of sarcasm, that Marvin need have no worry about being as good as Wayne–and he did not direct the film!

The relationship with Hawks, like that with Ford, extended beyond making pictures. Hawks gave the actor, as a token of appreciation for his work in Red River, a silver belt buckle shaped into the design of the “Red River D.” And another pleasant surprise greeted Wayne when he returned to the set of Rio Lobo after winning his Oscar Award. Under Hawks’s initiative, all actors and crew-members wore eye patches, a tribute to his one-eyed marshal in True Grit.

The Academy Award apparently confirmed what Hawks had known all along, “John Wayne has just come to be recognized for the good actor he is.” “I’ve always thought he was a good actor,” Hawks explained, “I always thought he could do things that other people can’t do.”

Rio Lobo served as Hawks’ final image. He was underappreciated in the United States until the late 1960s, when a new generation of reviewers reexamined his work, despite his great regard among French critics.

Hawks received an Honorary Oscar in 1974 for his four decades of effort, which was seen as restitution for never having been the winner of a true, competitive directorial Oscar. Only once, in 1941, for the Gary Cooper–starring military drama Sergeant York, was he nominated for Best Director. At home, he passed away in 1977.